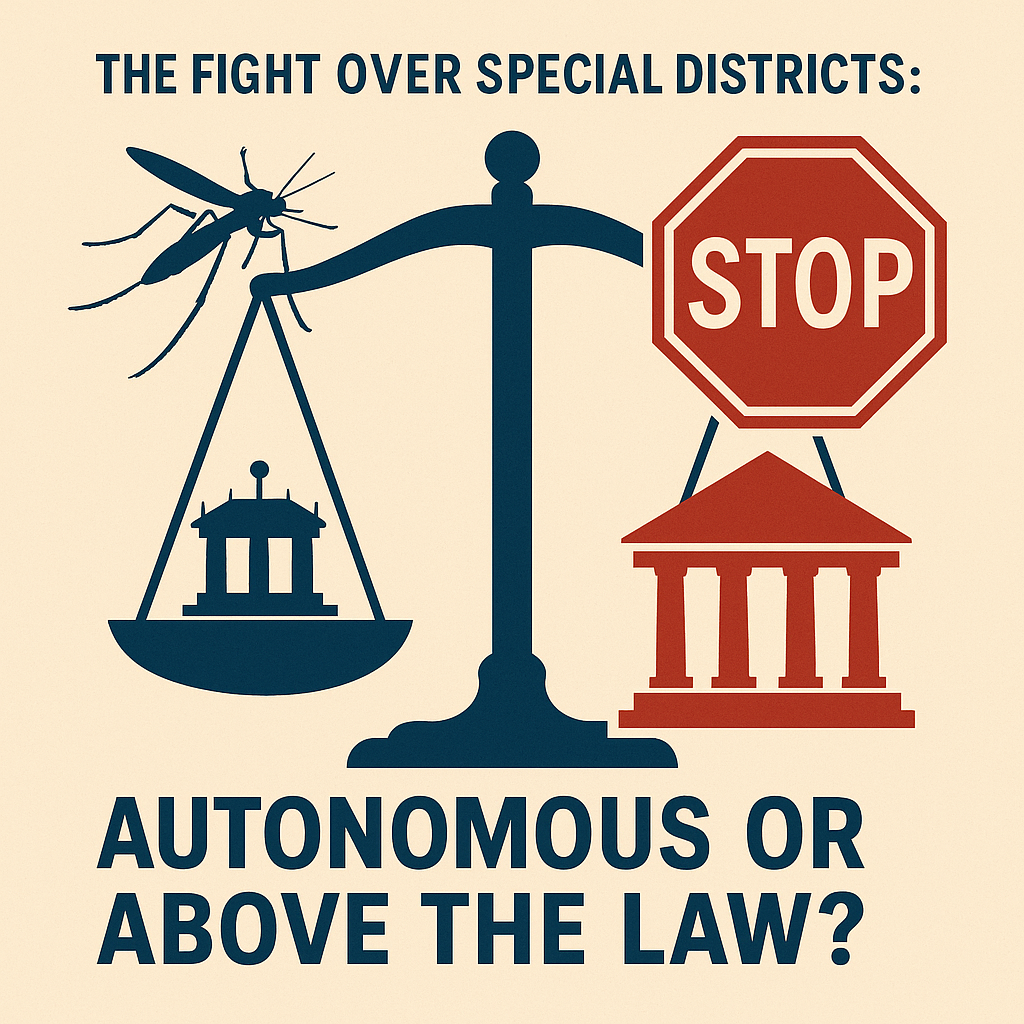

Mosquito district’s governance fight highlights broader dilemma: When do appointed commissions become immune to oversight?

Editorial

At the heart of the debate over appointed boards and special districts lies a fundamental question of representative government: how much authority can an elected legislative body delegate before it begins to surrender powers the constitution expects it to exercise? In Louisiana’s parish-president and council-mayor systems, councils hold the purse strings. They levy taxes, adopt budgets, and set spending priorities. Yet the state’s landscape is dotted with autonomous boards and districts — governing mosquito control, drainage, water, recreation and more — that operate with their own millages and policymaking authority, often beyond the direct reach of the officials voters elect.

The St. Tammany Parish Mosquito Abatement District highlights that tension. Its five-member volunteer board, appointed by the parish’s elected leadership, sets the district’s millage rate annually and manages a tax-funded operation with professional staff and millions in assets. That structure provides stability and shields technical work from day-to-day politics. But it also raises the question: when a board’s financial decisions stand apart from the council that levies taxes parish-wide, where does voter accountability ultimately reside?

Mandeville grappled with issue in 2023

That concern is not new in St. Tammany Parish. Mandeville confronted a similar issue in 2023, when city officials debated reviving a now-defunct Financial Oversight Committee with an expanded mandate. Critics argued the proposal would have effectively transferred core budgetary powers from the elected City Council to an appointed advisory body, forcing the council to adopt spending recommendations it did not originate and could not amend, thereby usurping the budgetary authority placed in council members by the voters. Opponents warned that such a shift could violate the separation of powers required by the city charter and the state constitution. The council ultimately rejected the proposal.

Both cases underscore a structural dilemma. Appointed commissions can offer expertise and continuity, and voters often approve the millages that fund them. But when those bodies set tax rates, influence spending or initiate policy in ways that bind or bypass the elected legislative branch, the risk is not just operational drift — it is democratic drift. The more authority shifts to entities that voters cannot remove, the harder it becomes to ensure transparency, enforce oversight or determine who is accountable when disputes arise.

Mosquitos fighting back

The tension surfaced most visibly with the mosquito abatement district, when a recent push by some parish council members to rein in spending and consolidate budgets led to an unsuccessful effort to remove several of the district’s commissioners. The dispute escalated after District Attorney Collin Sims publicly criticized the district’s spending and conduct, following the district’s decision to file a complaint with the Louisiana Attorney Disciplinary Board over Sims’ role on St. Tammany’s DOGE-style transparency committee, which had been reviewing its finances.

The district even filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to stop the parish from investigating the district’s finances, arguing the probe is politically motivated and intended to exert control over its dedicated tax dollars.

At the same time, a small but vocal group on social media — including some with ties to the district or who previously served on it — has been stoking public anger at elected officials for exercising their one remaining constitutional lever of control: the power to appoint and remove. The result is a narrative increasingly distorted and potentially dangerous.

Are we to accept, at face value, that once a committee, board or district is appointed and funded with its own long-term special tax, it is no longer answerable to the public or to the body that created it, or to any law enforcement official, not even a duly appointed financial review committee?

Autonomous or above the law?

It defies logic to argue that the parish’s chief law enforcement officer has a conflict of interest simply for reviewing the finances and operations of an appointed commission in the parish he serves. Likewise, it is untenable to claim that the appointing authority — the parish council — is somehow barred from examining the finances of a district funded with taxpayer dollars, the very taxpayers who elected them to provide said oversight in the first place.

The mosquito abatement district is a public body under Louisiana law, which holds that any board, committee, commission or entity created or appointed by an elected public body becomes a public body itself. As such, it is subject to the state’s Open Meetings Law (RS 42:11-28) and Public Records Act (RS 44:1-41), just as the parish council and every other public body is. Any resident has the right to request and obtain its financial records — a standard that applies all the more to the district attorney and the parish council.

Ultimately, voters should ask themselves a deeper question: when does the autonomy granted to a specialized district funded by dedicated tax dollars begin to resemble immunity from scrutiny? And if this publicly funded commission can reject oversight from both the parish council and the district attorney — even going to court to do so — has it not already crossed into a status no public body should ever hold: one that is, in practice, above the law?

-30-

This is so ignorant. They misused their authority, that is why we are angry with the council. This district did nothing wrong and spent funds the taxpayers wanted to better serve their community. The whole point of a special district is to keep the politicians out of it. If you look at the budget management of the council for the last 7 years, you will see them move around funds against the will of the public. Also, it is not up to the district attorney to tell anyone how to spend their money. It is up to the people and that elected board of regular people. We want our money to go to the mosquito abatement, the library board, and the fire districts and to them only! If the DA does not want to educate us on how he spends his funds, then we have every right to tell him we don’t want to fund his office!

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. The dismissive claim that the editorial is “so ignorant” suggests a fundamental misunderstanding of what was written, but it is still worth addressing the underlying misconceptions with facts.

Under Louisiana law, the mosquito abatement district is a public body. As such, it is subject to the Public Records Act and the Open Meetings Law — the same transparency requirements that apply to the parish council, the district attorney and every other public entity funded by taxpayers.

This editorial is not about whether the district spends money responsibly or whether voters support its mission. It is about the extraordinary notion that a publicly funded, publicly appointed body would go to court to block elected officials — and by extension, the public itself — from reviewing its financial records.

Public records belong to the public. They are not contingent on popularity, motive, or agreement with oversight. Suing to prevent lawful review does not protect democracy; it undermines it. If a court were to recklessly bar citizens — including the district attorney or the parish council — from accessing public records, the damage would extend far beyond this dispute, striking at the foundation of transparency and the freedoms on which representative government depends.

If you don’t like the district attorney or members of the council, you should exercise your right at the ballot box rather than advocating to deny your fellow citizens — even ones you disagree with — their right to lawful oversight by the officials they elected.

That was the point, and it is an important one.

LikeLike